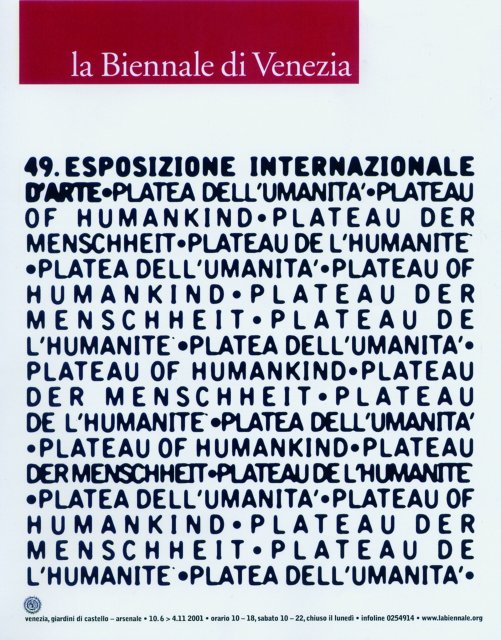

The 49th International Art Exhibition took place from June 10 to November 4, 2001, under the title Plateau of Humankind. It was directed, as the 1999 edition, by the Swiss critic Harald Szeemann and attracted over 243,400 visitors. Szeemann said that “No set theme was applied in choosing the artists; indeed, it is their work which decides the dimension of the event. The Venice Biennale hopes to serve as a raised platform offering a view over humankind”. A key work by Joseph Beuys, The End of the Twentieth Century, was exhibited. According to Szeemann, “It was Beuys above all who was the indefatigable spokesman for the concept of liberty”. Alongside Beuys, various other artists of the 20th century were exhibited: “Cy Twombly, whose generous gestures restore myth to the modern world; Richard Serra, the creator of a new concept of the monumental; Niele Toroni, the champion of painting as trace. Then come a number of those contemporary artists who have focused on the human figure – for example, Ron Mueck”.

The 50th edition of the International Art Exhibition was directed by Francesco Bonami and took place from June 15 to November 2, 2003. The title was Dreams and Conflicts. The Dictatorship of the Viewer. Bonami said the Exhibition, which attracted over 260,100 visitors, created “a polyphony of voices and thoughts: it is a large body in which different and independent spirits of contemporary art are shown”. Bonami in fact curated three exhibitions within this project: Delays and Revolutions (along with Daniel Birnbaum), Clandestine, and Pittura/Painting, a large retrospective about painting at the Venice Biennale from 1964 to the present day, which took place at the Museo Correr. Other exhibitions which were part of the overall project included The Zone, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, Fault Lines, curated by Gilane Tawadros, Individual Systems, curated by Igor Zabel, Zone of Urgency, curated by Hou Hanru, The Structure of Survival, curated by Carlos Basualdo, Contemporary Arab Representations, curated by Catherine David, The Everyday Altered, curated by Gabriel Orozco, and Utopia Station, curated by Molly Nesbit, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Rirkrit Tiravanija.

The 2005 edition (from June 12 to November 6) presented two distinct yet complementary exhibitions, The Experience of Art directed by María de Corral, and Always a Little Further directed by Rosa Martínez. For the first time in its history, the direction of the Biennale Art Exhibition was entrusted to two directors, both women, both from Spain. The two main exhibitions were complemented by 70 participating countries and 31 collateral events. Around 915,000 visitors attended the exhibitions in the Biennale venues and in other venues throughout Venice: 265,000 visitors at the two main shows, 370,000 visitors at the exhibitions of 40 countries in Venice, and a further 280,000 visitors at 31 collateral events.

The 52nd International Art Exhibition Think with the Senses - Feel with the Mind. Art in the Present Tense ran June 10 to November 21, 2007. 319,332 people attended the exhibition. This was the most attended Biennale of the past twenty-five years and one of the most visited in the whole history of the exhibition. The show took place in the 25,000 square-meters spread between the Giardini and the Arsenale, was directed by Robert Storr and included the extraordinary number of 76 National Participations and 34 Collateral Events. The 42 free entrance National Pavilions spread around the city of Venice, hosted in historical buildings and churches, have been visited by more than 827,000 people. The 34 free entrance Collateral Events set up around Venice and the lagoon islands attracted around 650,000 visitors.

The 53rd International Art Exhibition was directed in 2009 by Daniel Birnbaum and titled Making Worlds. The exhibition ran June 7 to November 22 and attracted 375,702 visitors, which resulted in an 18% increase compared to the previous edition.

Making Worlds consisted of one exhibition articulated in the venues of the renovated Central Pavilion at Giardini and at the Arsenale area, exhibiting more than 90 international artists featuring new works and new artistic languages. 77 National participations and 44 Collateral events were also part of the exhibition. The exhibition space of the Italian Pavilion at the Arsenale was doubled.

In 2011, it was Swiss art historian and critic Bice Curiger who curated the exhibition, titled ILLUMInations. This 54th edition of the International Art Exhibition was another record event, boasting an attendance of over 440,000 visitors (+18% when compared to the previous edition). 83 international artists were exhibited in the main section, 62 of them for the first time, 32 young artists were born after 1975 and 32 were women artists. A record number also for National participations, 89, and a remarkable presence of Collateral events, 37.

The Meetings on Art, a series of conversations with artists, critics and philosophers on the themes of the exhibition, brought the public of the Biennale close to personalities such as Laurie Anderson, Patti Smith, Achille Bonito Oliva, Germano Celant, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Okwui Enwezor, to name but a few. The special project, Biennale Sessions involved 31 national and international universities who visited the exhibition and organized seminars in a space offered for free by the Biennale.

The 55th International Art Exhibition, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, took place from 1 June to 24 November 2013; the Exhibition, titled The Encyclopedic Palace, got an extraordinary success, attracting over 475,000 visitors and confirming itself as the most visited art exhibition in Italy. More than 160 artists from 38 countries were included in the Exhibition. 88 National Participations were exhibited in the historical Pavilions at the Giardini, at the Arsenale and in the city of Venice; among these, 10 countries participated for the first time. The novelty was the participation of the Holy See with an exhibition at the Sale d'Armi in the Arsenale. The Italian Pavilion, located at the Tese delle Vergini in the Arsenale, was curated by Bartolomeo Pietromarchi and titled Vice versa after a concept theorized by Giorgio Agamben. The Venice Pavilion, titled Silk Mapand curated by Renzo Dubbini, returned to its original vocation, paying tribute to the "soft art", weaving, with five artists from Italy and the East. 47 Collateral Events took place in several locations in Venice. Throughout the Exhibition, the Meetings on Art were organized: a series of lectures, performances and debates, enriched by a project by the artist Marco Paolini, an installation titled FÉN ("hay").

The curator of the 56th International Art Exhibition in 2015 was the critic and writer Okwui Enwezor. The exhibition was titled All The World’s Futures and ran from 9 May to 22 November; the 2015 edition was particularly successful, attracting over 501,000 visitors and more than 8,000 accredited journalists. The show included 136 artists from 53 countries, of whom 89 were exhibited for the first time; of works on display, 159 were expressly realized for this year's edition. 89 National Participations were exhibited in the historical Pavilions at the Giardini, at the Arsenale and in the city of Venice, featuring 5 countries participating for the first time: Grenada, Mauritius, Mongolia, Mozambique, and Seychelles. 44 Collateral Events presented their exhibitions and initiatives in various locations across the city. The Arena in the Central Pavilion was the venue for an interdisciplinary programme of live events, the heart of which was the unabridged reading of Das Kapital by Karl Marx; conceived by the Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye, the Arena hosted recitals, film screenings, performances and public debates throughout the exhibition. The show also featured exhibitions from the Holy See (In Principio… la parola si fece carne at the Arsenale’s Sale d’Armi, curator: Micol Forti), the Italian Pavilion (Codice Italia, curator: Vincenzo Trione) and the Padiglione Venezia dedicated to applied arts (Guardando avanti. L’evoluzione dell’arte del fare. 9 storie dal Veneto: Digitale – non solo digitale, curator: Aldo Cibic). A collaboration between the La Biennale di Venezia and the Google Cultural Institute made it possible to put the exhibition on a digital platform that can be browsed online even after the end of the exhibition.

Future Dimension was the title of the International Art Exhibition in 1990, directed by Giovanni Carandente. The main exhibition set up in the Italian Pavilion, entitled Ambiente Berlin, was comprised of a vast collection of artists of a variety of nationalities that had worked in the German metropolis over recent decades. Emilio Vedova’s works (plurimi) of the Absurder Tagebuch cycle (1964) were particularly prominent at the beginning of the exhibition. A retrospective in Homage to Eduardo Chillida, the great Spanish sculptor who was awarded the Grand Prize in 1958, was set up in Ca’ Pesaro. Achille Bonito Oliva set up a special exhibition entitled Ubi Fluxus ibi Motus on the island of the Giudecca. Robert Rauschenberg, who had introduced Pop Art to Europe in 1964, exhibited one work in the Soviet Pavilion receiving much attention.

The Aperto section in the Arsenale Corderie was the cause of much attention and polemics. Members of the ecclesiastical community protested against the piece by the American group Grand Fury which addressed the subject of AIDS, whilst environmentalists opposed to an art work which involved live ants. The exhibition was temporarily closed due to tests carried out on Damien Hirst’s piece, a plexiglass box containing a dead cow. The formaldehyde solution, which was used to preserve the cow carcass, started to leak from its container.

The American artist Jeff Koons created life-size polychrome sculptures representing himself and his wife Ilona Staller. The Golden Lion for sculpture was awarded to Bernd and Hill Becher’s large format photographs of industrial archaeology, whilst Giovanni Anselmo’s work was presented the prize for painting. The American pavilion hosted Jenny Holzer’s evocative electronic writings and statements, which received the award for best national participation. The British sculptor Anish Kapoor received the Prize 2000 for young artist.

The 1993 edition curated by Achille Bonito Oliva was a great international and interdisciplanary overview. It included participation by 45 nations, featuring homage exhibitions dedicated to Francis Bacon, John Cage, and Peter Greenaway. The 45th edition was postponed until 1993 in order to make the next edition coincide with the centenary of the Biennale. Cardinal Points of the Arts was the title of this edition which was articulated in a series of 15 exhibitions. The exhibition at the Museo Correr designed by David Sylvester, featuring the works of Bacon (who had died the year before) was of particular significance. The floor surface of the German Pavilion had been broken up by artist Hans Haake, forcing the visitor to walk on the “debris of a nation”. The pavilion won the prize for best national participation. Similarly, the artist Ilja Kabakov transformed the Russian Pavilion into a kind of abandoned place filled with discarded material.

In 1995 the exhibition was entrusted to a non-Italian director for the first time, namely the Frenchman Jean Clair, who had set up a large exhibition on the theme of the face and the human body in the Palazzo Grassi. The exhibition, entitled Identity and Alterity, paid homage to the masters of the 20th Century, with works from some of the most important museums in the world. In its centenary year, the Biennale promoted events for each sector of activity.

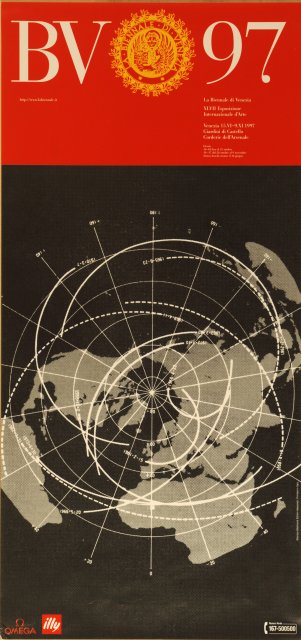

The 47th edition of 1997 Future, Present, and Past, curated by Germano Celant was an ideal reunion of three generations of artists from 1967 to 1997. The exhibition hosted 58 nations, and Golden Lions were awarded to Marina Abramovic and Gerard Richter.

In 1999, the Biennale initiated a large-scale renovation project on the historic naval buildings of the Arsenale in Venice (Artiglierie, Corderie, Gaggiandre, and Tese) transforming them into commanding exhibition spaces. The main international exhibition, previously confined to the limited spaces of the Italian Pavilion, could thus be laid out with greater ease. Both the 1999 and the 2001 editions were directed by Harald Szeemann, the former being entitled dAPERTutto (APERTO over ALL) the latter, Plateau of Humankind.

In 1979, the historian Giuseppe Galasso was nominated President of the Biennale, and critic Luigi Carluccio became Director of the Visual Arts sector. The director of the Theatre section Maurizio Scaparro, and that of Architecture, Paolo Portoghesi, led the first important initiatives of the decade. Scaparro linked the activities of the Biennale to the Venice Carnival with great success, and Portoghesi recuperated the Corderie of the Arsenale, a vast space until then left derelict, to host the exhibition on Postmodernism: La via novissima.

In the 1980s, the Art Exhibition was set up on specific themes: Art as Art (1982), Art in the Mirror (1984), and Art and Science (1986). Giovanni Carandente did not use the thematic structure in the 1990 edition which was instead, organised by sections: Ambiente Berlin and Aperto.

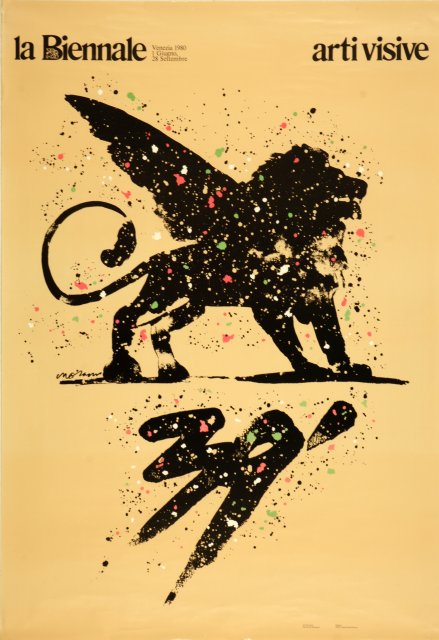

The International Art Exhibition of 1980 presented a diverse range of exhibitions, among which, one curated by Jean Leymarie dedicated to Balthus in the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, and another designed by Jiri Kotalik at Ca’ Pesaro (Modern Czechoslovakian Art in the Museums of Prague). Achille Bonito Oliva and Harald Szeemann created Aperto ’80, set up in the Magazzini del Sale in Dorsoduro. This new initiative was presented as a special section for young artists and was repeated in many succcessive editions. It was in this section that the Trans avant-garde movement, according to Bonito Oliva’s definition, came about with artists Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzo Cucchi, Nicola De Maria and Mimmo Paladino.

Art as Art: Persistence of the Art Work was the title of the exhibition conceived by Luigi Carluccio for the following edition (interrupted by his untimely death in Brazil in 1981). In the 1982 edition Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua, already General Secretary in the ‘60s, realized the projects that his predecessor had outlined. The exhibition that was to be dedicated to Matisse, presented only two works from the Hermitage. An exhibition was set up in homage to the sculptor Brancusi, and another, dedicated to Egon Schiele.In the summer of 1983, an exhibition entitled The Enchanted Mountains, with paintings by Michelangelo Antonioni was presented at the Museo Correr.

Paolo Portoghesi, the famous Italian architect took up his position as President from 1984 to 1992. The art historian Maurizio Calvesi was appointed director of the Visual Arts sector. The theme of the 1984 edition was Art and the Arts. History and the Present. The main exhibition hosted in the Palazzo Grassi was dedicated to The Arts in Vienna from the Secession to the fall of the Habsburg Empire. Two large exhibitions on current artistic issues were set up in the Giardini.

Art and Science was the theme of the 1986 edition, divided into two sections: the first entitled Between Past and Present, including Space, Art, Alchemy and Wunderkammer, the second The Age of Science including Art and Biology, Colour, Technology and Computer Science, and The Science of Art. It was a complicated and articulate edition which included an open-air sculpture exhibition set up in the Giardini. The work of artist Isamu Noguchi, presented by the United States, gained particular attention. In that year the management of the American Pavilion passed from the New York MOMA to the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation. Vincenzo Eulisse’s anti-racist initiative received much press coverage as he hung up black figures by butcher’s hooks, inaugurating it as the South African Pavilion.

The United States were also protagonists of the 1988 edition entitled The Place of the Artist. The Golden Lion was awarded to Jasper Johns, this was the first personal exhibition of the American artist who had participated in the Biennale since 1958. The Aperto section of the exhibition declared the American Barbara Bloom best young artist. Giovanni Carandente, director of the Visual Arts section in that year, set up some special exhibitions amongst which Ambiente Italia, dedicated to eight foreign artists active at that time in Italy, such as Twombly, Sol Lewitt, and Lüpertz.

Despite of the crisis derived from the turbulent 1960s, the Biennale also took place in 1970. The protests of '68 had left their mark: the Grand Prizes came to be abolished (although taken up again in 1986 with the Golden Lion award), the sales office was also eliminated, as it was considered an instrument for the commercialisation of art. The monographical and celebratory exhibitions were temporarily given up, and instead, thematic exhibitions such as Research and Planning and Art in Society were proposed. The General Secretary Umbro Apollonio and Dietrich Mahlow curated the special exhibition Proposal for an Experimental Exhibition, the aim being to "present some problematics in the arts", lining up works by Malevich, Duchamp, Man Ray, and Albers.

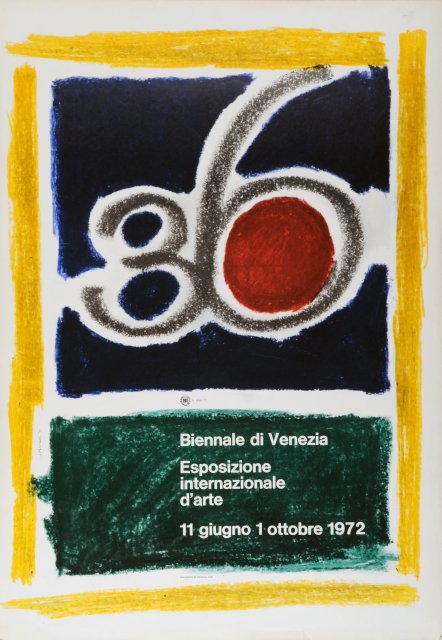

In 1971 Mario Penelope was nominated Special Commissioner for Fine Arts, and immediately organised an exhibition entitled Aspects of European Graphics at Ca' Pesaro. Penelope created a much appreciated Biennale in 1972, which was articulated in a series of exhibitions. He also proposed a comprehensive theme for the first time entitled Work and Behaviour . During this Biennale, ten thousand butterflies were liberated from a large wooden chest in Saint Mark's Square. Gino De Dominicis, just twenty-five years old at the time, "exhibited" a boy affected by Down's Syndrome, hanging a sign from his neck reading "Second solution for immortality: the universe is immobile". This caused a major scandal and public protests against this "cynicism" provoked interrogations in Italian parliament.

The statute of the Venice Biennale remained a major problem to be resolved: there were many requests to up-date the Biennale as an institution. The new statute of the Biennale was approved by Italian parliament on 26th July, 1973, but it was not until 20th March, 1974, that the 18 members of the Board came to be nominated.

President Carlo Ripa di Meana made a sensational decision to dedicate the entire 1974 edition to Chile, setting up exhibitions of painted panels (murales), and organising theatrical performances and concerts. This edition was perhaps the largest and most resonant cultural protest against the Chilean dictator, General Pinochet. Many Italian and foreign painters such as Sebastian Matta and Emilio Vedova, filled the Venetian campi with murales celebrating the freedom of the Chilean people: these many artists constituted the Salvador Allende Brigade.

Ortensia Allende, the widow of the assassinated Chilean president, also attended the inaugural ceremonies of the Biennale of 1974 in Venice, which resulted in a very crowded event held solemnly at the Duke's Palace instead of at the Giardini. It was such an unusual edition of the Biennale that not even the traditional Roman numeration was assigned. No catalogue was printed, but was substituted instead by photocopied booklets regarding each exhibition or performance.

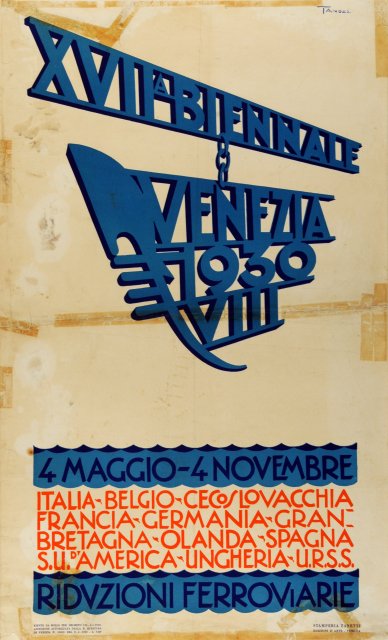

The Biennale exhibitions of the 1960s started with a crescendo of polemics both due to the great number of artists invited, and to what came to be defined as the "excessive power of the critic", which was seen to impose modes and styles. The opinion of many was that it was the critic that determined the rise of the Informal movement at the Biennale in 1960. Grand Awards for painting were presented to the French artists Fautrier and Hartung, and to the Venetian painter Emilio Vedova, for whom this award meant international recognition.

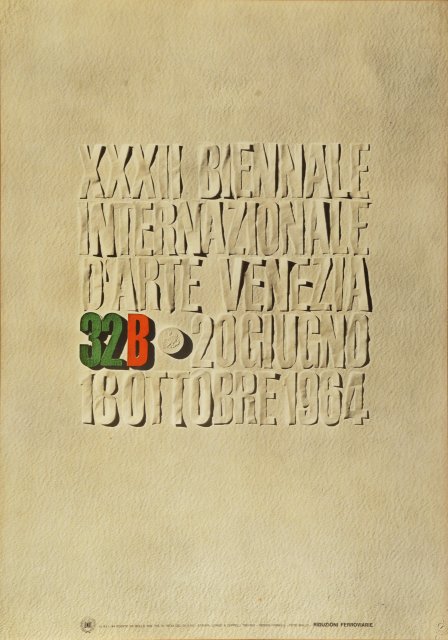

The sensational arrival of Pop Art in 1964 gave new life to the Biennale. The prize for foreign artist was awarded to Robert Rauschenberg, shifting the focus of pictorial research from Europe to the United States of America. Pop Art was also represented in Venice by Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenburg. A collateral exhibition of pop artists was planned and realized by Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend in the ex-American Consulate at San Gregorio. This additional exhibition proved America's commitment to Pop Art. The General Secretary Gian Alberto Dell'Acqua, claimed that this additional exhibition at San Gregorio was necessary, due to the sheer size and quantity of the works. The Grand Prize awarded to Rauschenberg provoked much heated discussion amongst the members of the international jury. The French accused the Biennale of introducing American "cultural colonisation". As Rauschenberg exhibited only four paintings in the official pavilion, a few other works exhibited at San Gregorio were quickly transferred to the Giardini as soon as news of the prize had spread. The stir that Pop Art had caused amongst the European press and critics somewhat cast a shadow over the other exhibitions included in the 1964 edition.

After Pop Art, the Biennale of 1966 seemed almost a return to rationality and rigour. It was the year of optical and kinetic art, and arte programmata . The exhibition spaces of the Giardini were dominated with installations by the Argentinian artist Julio Le Parc, awarded the prize for painting, and the work of the Venezuelan artist Raphael Soto. In the Italian section, Lucio Fontana's "cuts" and Alberto Viani's plaster sculptures were also awarded prizes. Amongst the retrospectives, the most notable were those dedicated to Umberto Boccioni and Giorgio Morandi, who died during the period of the vernissage in 1964.

The next Biennale was struck by the 1968 protests. Demonstrations and disorder characterised the 34th edition, artists from many different countries took part in the manifestations, and as a sign of solidarity, either covered up their works or turned them over. Some historical exhibitions were not even opened. The central pavilion hosted a very ambitious exhibition entitled Lines of Research with works by Malevich, Duchamp, Calder, Rauschenberg, and Gorky. The inaguration took place without any major disruption. Grand Prizes were awarded to Schoffer and Riley for foreign artist participation, and to Gianni Colombo and Pino Pascali (who died one month previously) for the Italian section.

After the Second World War the Biennale resumed activity with one of its favourite subjects: French Impressionism, presented by Roberto Longhi in a memorable retrospective. The 24th Biennale in 1948 was particularly significant due to its reconsideration of the avant-garde, made possible also by the commitment of the foreign pavilions. The General Secretary Rodolfo Pallucchini organised the first five Biennale exhibitions after the War (from 1948 to 1956). This period of time enabled him to present an overall view of European avant-garde, which still however, excluded Dadaism. Above all, he succeeded in rendering contemporary art more accessible to the Italian public.The two major events of 1948 were Picasso's retrospective exhibition (first appearing in the Biennale at the age of 67, presented by Guttuso), and the exhibition of the Peggy Guggenheim collection featuring 136 works by 73 artists, presented by Giulio Carlo Argan. In following years more avant-garde retrospectives were presented. At this time the importance of the avant-garde movement was fully recognised: prizes were awarded to Braque (1948), Matisse (1950), Dufy (1952), Ernst, and Arp (1954).

The 1950 edition was also a success, featuring four significant exhibitions on Fauves, Cubism, and Futurism, and the Der Blaue Reiter movement. The astonishing pictorial violence of the Mexican Pavilion was a revelation; featuring the "four greats": Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Riviera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo. In 1952 Pallucchini proposed a comparative exhibition featuring Italian Divisionism (Previati, Pellizza da Volpedo, and Segantini) alongside French Pointillism (Pissarro, Signac, and Seurat). A major exhibition of Toulouse-Lautrec prints was set up in the Napoleonic Hall.

In the meantime new trends broke out. The American Pavilion presented Jackson Pollock's action painting. The special prize for sculpture was awarded to Calder in 1952, and Chadwick in 1956. The Biennale of 1954 featured Surrealism. The works of Courbet, Munch, Klee, and Magritte were exhibited in their respective pavilions. Under the direction of the new General Secretary Gian Alberto Dell'Acqua, who was in charge from 1958 to 1968, the Biennale contributed significantly to the diffusion of contemporary art.

THE EXHIBITION IN 1948

The 24th Biennale exhibition in 1948 was particularly significant due to its reconsideration of the avant-garde, also made possible thanks to the commitment of the foreign pavilions. The General Secretary Rodolfo Pallucchini, capable of interpreting these demands, organised the first five Biennale editions after the war (from 1948 to 1956). This long time span allowed him to present quite a comprehensive view of European avant-guardism (from which Dadaism still remained excluded). He thus succeeded in rendering contemporary art more accessible to the Italian public. Two major events were the retrospective of Picasso with 19 paintings (his first appearance at the Biennale at the age of 67) presented by Guttuso, and the Peggy Guggenheim collection (136 works by 73 artists) presented by Giulio Carlo Argan. This entered contemporary art into lively debate, thanks to the presence of the most advanced trends, such as Cubism and Surrealism. Ernst, Dali, Kandinsky, Klee, Mirò, and Mondrian were some of the names that characterised the 24th Biennale.

Only fifteen countries participated in this edition, as many nations were still recovering from the war. Empty pavilions were used to host special exhibitions (such as Impressionism in the German Pavilion, and the Guggenheim collection in the Greek Pavilion). An exhibition entitle Three Italian Metaphysical Painters featured works by Carrà, Morandi, and De Chirico. The latter however, did not agree with the curatorial choices of Francesco Arcangeli, and opened up a law suit, which was only to be concluded in 1955. De Chirico refused to exhibit at the Biennale until 1956, when he presented 36 paintings in a personal exhibition. Giuseppe Marchiori curated an exhibition entitled Il Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, from which the Realist movement and the Group of Eight emerged in following years. A significant Impressionist Exhibition presented works by Monet, Sisley, Cézanne, Degas, Gaugain, and Van Gogh.

The national pavilions also organised important exhibitions. The French Pavilion lined up personal collections of Maillol, Braque, and Chagall, while Austria presented Egon Schiele and the sculptor Fritz Wotruba, using the Yugoslavian Pavilion for a comprehensive exhibition of Oskar Kokoschkla. The British Pavilion brought Turner and Henry Moore to Venice, the Belgian Pavilion, Ensor and Permeke. The central pavilion featured a personal exhibition of Paul Klee and another dedicated to German artists repudiated by Nazism. In the Italian section, amongst others, there were retrospectives of Arturo Martini and Gino Rossi, as well as personal exhibitions of Massimo Campigli, Filippo De Pisis, and Mino Maccari.

The great Venetian architect Carlo Scarpa carried out a series of particularly interesting installations and interventions for the Biennale during the post-war period from 1948 to 1972.

In 1948 Scarpa curated the installation of the Guggenheim collection, as well as the distinctive lay out of the Paul Klee room. His work linked contemporary architecture to the specificity of the Venetian environment and its traditional craftsmanship.

In 1958 Scarpa designed the Alberto Viani room, and around forty other rooms in 1960. Futhermore, he designed the interior of the Italian Pavilion in 1962, 1964, 1966 and 1968, building a false ceiling in the main hall, thus doubling the exhibition space. His installation of the Fontana room became famous in 1966, featuring cubic pedestals specifically designed for the artist's sinuous sculptures. In 1972, Scarpa concluded the series of interventions, characterised by what Corboz defined as a "muséographie poétique".

In the period after the First World War, the Biennale showed an increasing interest towards the most innovative artistic trends, thanks to the new General Secretary Vittorio Pica, that had been interested in the Impressionists since 1908. In 1920 Paul Signac, the curator of the French Pavilion, exhibited 17 of his own works and other works by Cézanne, Seurat, Redon, Matisse, and Bonnard, whilst the Dutch Pavilion proposed a retrospective of Van Gogh, and the Swiss Pavilion, Hodler.

In 1922 Pica presented the first retrospective of Modigliani's work, and in that same year organised an exhibition of African sculpture, which both caused much controversy. The term "primitive" was used in a pejorative sense for African sculpture, whilst Modigliani's disorganised life was emphasised. However, in the second retrospective in 1930, there were no traces of such criticism. Furthermore, Vittorio Pica was able to impose his decision to exhibit six watercolours by Van Dongen, in spite of the opposition by the Board and of the new Mayor of Venice, Davide Giordano.

Meanwhile in 1920 Filippo Grimani had lost the title of Mayor of Venice and likewise the position of President of the Biennale. The Giordano Commitee, worried by the new daring artistic trends embraced by Pica, set up a Board of 7 members (becoming 8 in 1924 and 13 in 1926) to join the General Secretary. In 1926 , Pica was forced to resign for health reasons and Count Pietro Orsi became Mayor of Venice and President of the Biennale. He appointed the new General Secretary, Antonio Maraini. In 1928 the Archive of the Biennale was established under the name of the Historical Institute of Contemporary Art.

INSTALLATION AND DECORATION IN THE EARLY YEARS

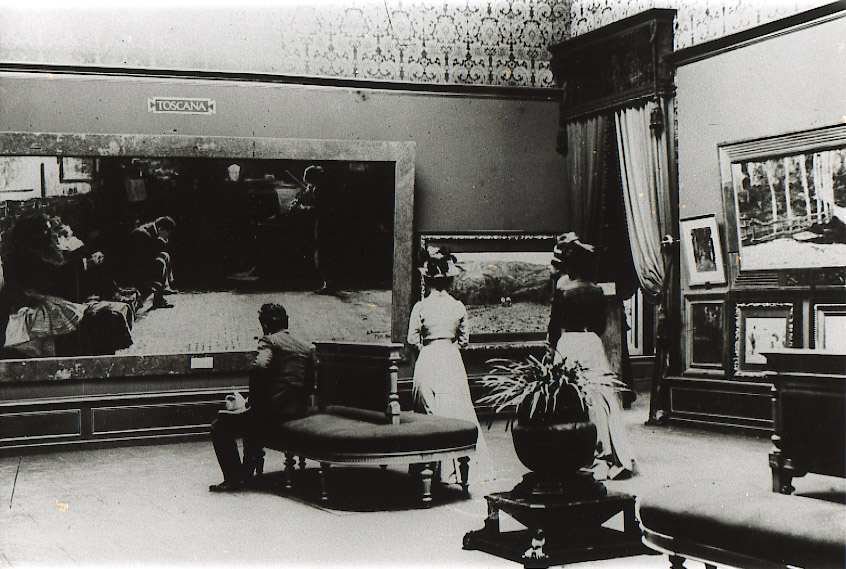

The first exhibitions generally followed contemporary trends in interior design and furnishing found in Salons and picture galleries, after the prevailing fashion of the neoclassical style of museums. Romolo Bazzoni, author of the first history of the Biennale, noted that "in such a large space, paintings and statues didn't always show up well".

Since 1901 the Biennale studied the most suitable solutions for the positioning of the works to be exhibited, mainly in the somewhat disorganised central pavilion. In that year the first General Secretary Antonio Fradeletto introduced decoration as an autonomous artistic style, with the interior design of seven regional Italian rooms. In 1907, Giulio Aristide Sartorio decorated the central hall with scenes of classical mythology. He painted four panels, each seven metres long and five metres high, two for each wall of the room. A few years later, on the event of the Biennale of 1912, they came to be substituted by those by the painter Pieretto Bianco.

The difficult relationship between the decoration, placing of the pieces, lighting, and furnishings, was dealt with with increasing awareness and originality thanks to international examples, influenced by exhibitions in Stockholm and Brussels and the Viennese Secession . Since 1905, the Austrian and German rooms came to be exemplary in their design by the work of leading figures in furnishing such as Emanuel Seidl, Bruno Paul, and Joseph Urban. The Austrian hall was designed by E.I Wimmer in 1910. The room, which was later to become famous, hosted a personal exhibition of Klimt.

In 1907, Galileo Chini, one of the most active Italian decorators, was inspired by the Art Nouveau style for the decoration of the rooms hosting the Symbolist exhibition The Art of Dream. In 1909, on the event of the eighth Biennale, Fradeletto wished to try another experiment with mural decoration, this time directly painted onto the walls of the domed entrance hall of the main pavilion. The execution of the works was again entrusted to Chini, who depicted the most illustrious periods of civilisation and art painted onto the eight segments of the dome. In 1914 Chini also decorated the central hall on the event of the eleventh Biennale, commissioned to substitute the panels painted by Pieretto Bianco in 1911.

THE FIRST FOREIGN PAVILIONS

The first foreign pavilion was that of Belgium built in 1907 under the initiative of Prof. Fierens-Gevaert, the Belgian general director of Fine arts. The project for the building and interior decoration was carried out by the architect Léon Sneyers. In 1930 two rooms were added to either side of the central hall, and in 1948 the Venetian architect Virgilio Vallot designed the new façade.

Three new pavilions were built for the eighth Biennale of 1909. The British Pavilion was not entirely built from scratch, instead the architect Edwin Alfred Rickards modernised an existing building, its interior decoration carried out by Frank Brangwyn. The German pavilion, designed by Daniele Donghi, an architect of the Venice City Council, was built next to the British Pavilion. The pavilion initially hosted Bavarian art, and from 1912, works from all over Germany. Closed during the war, it reopened in 1922 exhibiting works from the then Federal Republic of the German Reich. Property of the Venice City Council, in 1938 it was taken over by the German goverment, and rebuilt under Hitler's order substituted by a more modern design by Ernst Haiger. The architect and sculptor Géza Maróti, inspired by the tradition of Hungarian history and art designed the Hungarian Pavilion in 1909. The mosaics were realised by Miksa Roth, based on drawings by A. Korosfoi. At the Biennale of 1948, an exhibition was set up elsewhere to allow for the restoration of the damaged pavilion, but continued delays meant that it remained closed until 1958, when Agost Benkhard partially reconstructed it.

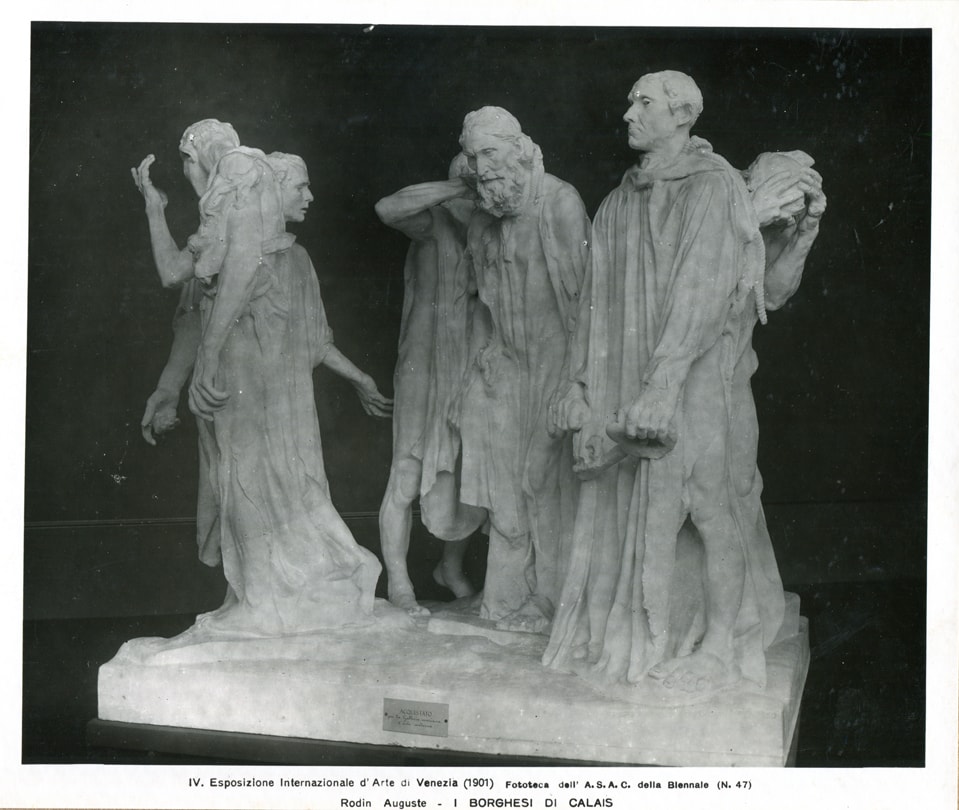

The French and Swedish pavilions were built in 1912, both designed and constructed by the Biennale. The French pavilion was inaugurated with a personal exhibition of Rodin's work. In 1914, the Swedish Pavilion was handed over to the Netherlands. In 1954 the Dutch pavilion was demolished and reconstructed on the same site, designed by Gerrit Rietveld, one of the architects belonging to the De Stijl movement. The Russian pavilion was built by Aleksej V. Scusev in 1914.

BIENNALE EXHIBITIONS ABROAD

With the arrival of Giuseppe Volpi as president (1930), the Biennale began to organise exhibitions of Italian art abroad, and to curate the Italian participation in various important international exhibitions. In 1932 a major Italian art exhibition was set up in New York, and later in other American cities. In 1933 the same initiative was realised in Europe, with exhibitions presented in various cities around Germany.

In 1935 the Biennale organised an "exhibition of modern and contemporary art" in Paris, and a sculpture exhibition in Vienna. In following years, figurative art exhibitions were promoted in Budapest, Amsterdam, and Sydney. One of these exhibitions was set up in five cities between Bucharest and Athens, before reaching India. A touring exhibition of Italian landscapes was set up in Warsaw in the autumn of 1937; later moving to Tallin where it remained until spring 1938.

In the postwar period, following the organisation of an exhbition in Switzerland in 1947, the Biennale curated the Italian participation in other significant international biennial exhibitions such as that of Alexandria and São Paulo. The Biennale continued to promote these initiatives abroad until the mid 1970s.

French art, which had been somewhat neglected in the first exhibitions, was finally included in the 4th Biennale of 1901 , through an Exhibition of French landscape painting. Works by Corot and Millet landed in Venice, and Rodin's twenty sculptures of his personal exhibition received considerable success. Two novelties were introduced within the fifth Biennale in 1903: one being the inclusion of the decorative arts, furnishings in particular, the other being the Salon des Réfusées, following a dramatic protest due to the verdict of selection, which excluded 823 works out of 963.

French Impressionism, by this time a trend already established in Europe, was not considered in this period. There was instead an inclusion of American art: Sargent was presented a medal in 1907 and Barlett held a personal exhibtion in 1909. In 1907, thanks to the intervention of Diaghilev, the Biennale invited both Repin, the Tolstoian witness of Russian tradition and Bakst, a famous costume and set designer for the Ballets Russes. It was not however, until 1910, that the presence of renowned international artists at the Biennale was so strong: a splendid Klimt room contrasted that of Renoir, also included in the exhibition were the retrospectives of Courbet and Monticelli. Expressionism, which was born in Dresden in 1903, was presented in Venice in 1914 with an Ensor personal exhibition.

Italian art was predominantly represented by 19th Century works both in the arrangement of the exhibits by region (1901), and in the retrospectives dedicated to Fontanesi, Fattori, Signorini, and Cremona. This trend came alongside the somewhat dated Symbolist style. The Art of Dream exhibition of 1907, also including foreign simbolists, was a significant example of this. From 1908 onwards, a few young artists exhibiting in Ca' Pesaro and grouped together by the critic Nino Barbantini, strongly opposed to this trend which they considered to be too academic. It was only in 1914 that Medardo Rosso would have his personal exhibition at the Biennale.

From 1907 on, Fradeletto supported the building of the foreign pavilions (7 of them were already built before World War I). The ninth Biennale was held in 1910, so as not to coincide with the great Art Exhbition which was to take place in Rome, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Kingdom of Italy. The Biennale then took place twice yearly until the interruption from 1914 to 1920 due to the First World War.

There was a particular relationship between the Biennale and Picasso: In 1905, Fradeletto, the General Secretary, had one of his pieces removed from the Spanish Pavilion, as he feared that Picasso's innovative artistic language may cause a public scandal. Picasso's works were only to be exhibited at the Biennale in 1948, thanks to a retrospective curated by Guttuso.

THE CA' PESARO GALLERY

The International Gallery of Modern Art in Venice was founded by Prince Alberto Giovannelli, who, at the second Biennale in 1897, bought six art works of both Italian and foreign artists which he then donated to the City Council of Venice. Others followed his example, such as King Vittorio Emanuele III who also contributed four canvases. The first premises of the gallery were at Ca' Foscari. Ca' Pesaro, a sixteenth century palace on the Grand Canal designed by Baldassarre Longhena, became property of the City Council of Venice in 1899, following the death of Duchess Felicita Bevilacqua La Masa who expressed the wish to create a permanent exhibition space for the work of young artists. The Gallery of Modern Art was then moved there, and the opening took place on 18th May, 1902.

The management of Ca' Pesaro was entrusted to the Secretariat of the Biennale, but in 1907, considering the growing importance of the gallery, it was decided that a director be appointed. Nino Barbantini, a young man of just 23 years of age, took up the position. He immediately started to study a suitable positioning of the art works, choosing to organise the works into national groups. The conflict between the Biennale and Barbantini started when Ca' Pesaro hosted its first exhibition in 1908. Fradeletto, the General Secretary of the Biennale, did not appreciate the young director's initiative. According to the wishes of Duchess Bevilacqua, Ca' Pesaro should only exhibit the work of young artists, not veterans of the Biennale. There was a polemic debate about the use of the winged Lion of Saint Mark, which was already the logo of the Biennale, on the poster for the Ca' Pesaro exhibition. The annual exhibitions that took place at Ca' Pesaro from 1909 to 1913, merely accentuated its independence, and the antagonism with the Biennale grew stronger due to the diverse artistic criteria that the two institutions adopted. These disagreements became all the more bitter in June 1914, when a group of artists refused by the Biennale, organised a polemic exhibition at the Hotel Excelsior at Lido entitled an "Exhibition of some artists refused by the Venice Biennale". That year, out of the 621 artists who presented their work at the Biennale, only 114 were accepted. Following the exhibition of the "refusés", the rivalry between the two institutions began to fade away.

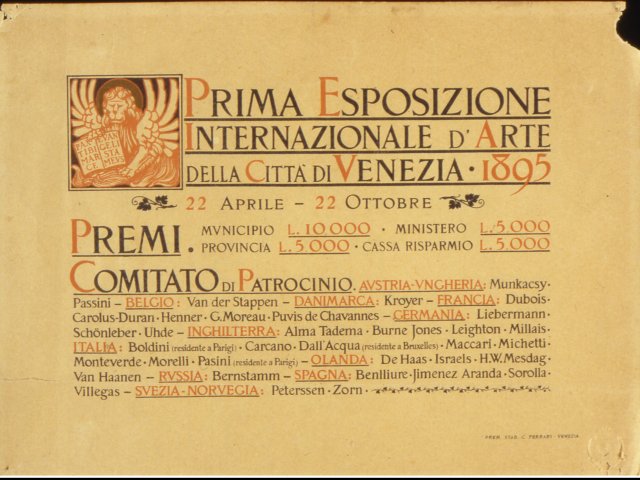

The Venice Biennale was born by a resolution by the City Council on 19th April 1893, which proposed the founding of a "biennial national artistic exhibition" to take place in the following year, to celebrate the silver anniversary of King Umberto and Margherita of Savoy. The event in fact took place two years later, on 30th April, 1895 . In the period between the idea and its realisation, the commitment of the then Mayor of Venice Riccardo Selvatico turned out to be successful. He strongly wished to transform the artists' evening meetings at Caffè Florian into a prestigious international exhibition.

The organisation of the event started by the studying of a statute devised by a specially appointed commission, and inspired by the Secession in Munich. The decision was taken not only to invite major foreign and Italian artists, but to include also the works of uninvited Italian painters and sculptors. Each artist could participate with no more than two works, previously unexhibited in Italy. Three commitees were formed: one of Venetian artists to develop the program of the exhibition, another for promotion, and another for the Press. Antonio Fradeletto was appointed General Secretary and became one of the most influential figures of the period. Thanks to his diplomatic skill he was involved in the selection of the artists, the installation of the exhibition, and later the construction of the foreign pavilions.

The pavilion which was to host the first exhibition was feverishly built in the public gardens in Castello, just in time for the opening ceremony with the presence of King and Queen of Savoy, and the enthusiastic participation of the Venetian public. There were over 200,000 visitors at the first International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice (later to be called the Biennale because it took place every two years). The special return train tickets, which included entrance to the exhibition, contributed to this great success.

The major Prize, being the result of an impartial judgement, was attributed both to Giovanni Segantini, for his Return to Native Village, and to Francesco Paolo Michetti for his painting Jorio's Daughter: since two artistic trends were recognised, the most representative personalities were commended. But the work that raised the biggest stirr, due of its risqué subject matter, was Giacomo Grosso's Supreme Meeting, depicting a dead man surrounded by nude female figures. This piece was to win a prize by a popular referendum which took place at the closing of the exhibiton.

In 1897 the new Mayor Filippo Grimani substituted Selvatico as the President of the Biennale. On the event of the second exhibition of that year, together with the foundation of the Galleria d'Arte Moderna of Venice, the jury opted instead for the purchase of the art works for the benefit of national and local galleries. The same jury set up a Critic's Prize, with the intention of improving the promotion of the event. On the one hand, this prize stimulated the production of articles and reviews, thus improving the quality of Italian art criticism in that period, and on the other, reached a milestone in the history of contemporary art criticism.

French art was quite neglected in the first Biennale exhibitions, whereas the priviledged relationships with the Secession drew much attention to German art. Already in 1899, Klimt's Judith II had been presented. In the meantime, the Biennale allowed a select few Italian artists, such as Michetti and Sartorio, the opportunity to exhibit in personal rooms, thus inaugurating the new formula of the personal exhibition which was to be adopted as of the third Biennale Exhibition in 1899.

THE GROSSO CASE

A painting included in the first International Art Exhibition of the City of Venice in 1895 stirred much commotion and curiosity: it was Giacomo Grosso's Supreme Meeting, a then famous artist, and a professor at the Accademia Albertina in Turin.

The president of the Academy, the Count of Sambuy, recommended that the Mayor Riccardo Selvatico placed “the painting of audacious and fantastical composition” in a good light. Since Grosso was one of the artists invited to the Biennale, and since the first citizen knew his value well, Selvatico reassured the Count about his intentions, but he could not foresee “which, and how many troubles that painting would have caused him!” (as Romolo Bazzoni noted in his history of the Biennale).

The work reached the exhibiton on the 10th April 1895. As soon as it was removed from its packing case, it astonished everyone who saw it. The painting depicted a coffin surrounded by five nude female figures. The painter intended to represent the end of a Don Juan. For those whose task was to hang the artwork, the only worry came from the strong contrast of colours that could disturb the viewing of the surrounding paintings, whereas for the managers of the Exhibition, the unease was due to the subject matter of the painting, which could offend the morality of the visitors.

The following day however, the Patriarch of Venice, Giuseppe Sarto (later to become Pope Pious X), wrote a letter to Selvatico asking that the work which he had heard about, should not be exhibited. The Mayor replied wih the verdict from the Commission and indeed, the work participated in the first exhibition, although it was placed in a rather isolated room.

The clerical press cried out about the scandal, the foreign and Italian press also mentioned the circumstance, fueling public curiosity all the more. At the end of the Exhibition, the prize assigned by a popular poll was awarded to Grosso’s painting, which resulted in yet further polemic.

A company later bought the painting in order to make it more widely known in the United States, where its reputation had already landed. But the Supreme Meeting was destroyed in a fire whilst crossing the ocean.